How Cannabis Traveled from California’s Underground to the Heart of American Culture

A chronicle in 10 chapters—from borderlands and beat poets to boardrooms and billboards.

The epidemic didn’t have a name at first.

Just a pattern—young men in San Francisco, New York, and Los Angeles showing up in emergency rooms with pneumonia, rare cancers, and no immune system to fight back. Doctors called it GRID: Gay-Related Immune Deficiency. The newspapers barely mentioned it.

By 1983, it had a name—AIDS—and the numbers were rising fast. There were no antivirals. No funding. No plan. Hospitals were full of patients no one knew how to treat. Some staff refused to touch them. Families stopped visiting. Politicians stayed quiet.

People wasted away in real time. Healthy men dropped to 110 pounds. They couldn’t eat. Couldn’t sleep. Couldn’t stop the pain. The government offered funeral statistics. The pharmaceutical companies offered nothing at all.

So the community did what it always had to do. It helped itself.

Someone brought in a joint.

It wasn’t a cure. It wasn’t a campaign. It just helped. It eased the nausea. Brought back appetite. Settled nerves. Made the pain tolerable enough to make it to the next day.

They didn’t ask permission. They didn’t talk about laws. They called it medicine. And they were right.

***

San Francisco General Hospital, Ward 86. 1987.

The breakroom smelled like old coffee, antiseptic, and panic. Nobody said that last part out loud, but it was always there.

Dr. Klein didn’t sit right away. Just stood with his back to the microwave, coat still on. “Patient in 203 is wasting again,” he said. “Down nine pounds this month.”

The nurse—forty years in, too tired for debates—tapped her pen against a clipboard she wasn’t using. “Half these guys haven’t eaten in days,” she said. “One joint and they ask for toast.”

No one laughed. They all knew it was true.

Susan, the caseworker, set her paper cup down and opened a folder. Inside was a loose sheet with seven names in ballpoint. “These are the ones who asked me directly. I didn’t give them anything. I just… told them what I’d heard.”

The younger intern, Rodriguez, shifted in his seat. He’d been on the floor three weeks. “What do we tell the families?”

“You don’t tell them anything,” Klein said. “You listen. You give them the number for that store on Church Street. And you don’t put it in the chart.”

Rodriguez hesitated. “What if they ask if it’s safe?”

“Safer than starving to death.”

“So we’re just ignoring it now?”

Klein finally sat. He looked tired in a way that sleep didn’t fix. “Not ignoring” he said. “Just not reporting.”

They didn’t call it a policy. There wasn’t a vote. But the room agreed anyway.

Nobody was writing prescriptions. But nobody was stopping anything, either. If someone rolled a joint by the bedside and the vitals improved, that was enough. Some nurses walked out of the room and came back slower. Some doctors didn’t look too closely at what came out of a coat pocket.

No memos. No meetings. Just people adjusting around the truth.

When they stood up and walked out, nothing had changed officially.

But they all knew.

***

Word spread quietly.

Room to room, then block to block.

In San Francisco, friends started cooking for each other, checking in, bringing what little worked. Cannabis wasn’t a secret anymore. It was a tool, passed like food or advice.

Dennis Peron had already been dealing in the Castro for years. When his partner died of AIDS in 1990, he stopped waiting for change. He opened the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club, the first public dispensary in the country. No license. No protection. Just a door and a mission.

People came with nothing. They left with what they needed—joints, brownies, loose flower. The only rule was: if you’re sick, you don’t pay.

Others joined in. Volunteers. Nurses. Former patients. Some cooked. Some delivered. Some just sat with the dying.

They didn’t call it a movement. They weren’t asking for legalization. They were offering medicine, because no one else would.

And they knew the risk. But they did it anyway.

It didn’t stop with AIDS.

Within a year, cancer patients began showing up at the Buyers Club. They came pale and thin, wearing sunglasses indoors, wrapped in sweaters no matter the weather. They didn’t care about politics. They just wanted to eat. To sleep. To feel normal for a few hours.

Then came the glaucoma patients—older men, mostly, who couldn’t stand the pressure in their eyes and didn’t want another surgery.

Then came the parents. Quiet at first. Careful. Asking questions. Reading case reports. They’d heard about children with epilepsy who were finally sleeping through the night after a drop of cannabis oil. They didn’t want to believe it, but nothing else had worked.

What started in the shadow of one crisis became the outline of something bigger.

Doctors were still cautious. Lawmakers stayed silent. But the stories kept stacking up. And slowly, the research began to follow. Animal studies. Anecdotal trials. Then human data—scattered, small, but enough to suggest what patients already knew.

The plant wasn’t just helping. It was working.

It had stopped being a loophole. It had become a lifeline.

The arrests didn’t stop either.

Brownie Mary was picked up three times—once with over two dozen cannabis brownies in Tupperware meant for AIDS patients. She was 70, wore orthopedic shoes, and baked in her spare time between hospital volunteer shifts. The city didn’t care. They charged her anyway.

The Buyers Club was raided by police in flak vests. Dennis Peron was dragged into court more than once. His defense was simple: “I sell medicine to sick people.”

Phones were tapped. Surveillance vans parked down the block. Letters came with no return address.

But the line outside the door didn’t get shorter.

Cancer patients still showed up. So did parents, veterans, and hospice nurses. The media started paying attention. So did doctors. Even a few lawmakers began to admit, quietly, that this wasn’t a drug ring. It was a response.

This wasn’t about breaking laws. It was about saving time—for people who didn’t have much left.

And for more and more of the public, it was starting to look less like crime—and more like care.

By the mid-1990s, the media had started to change its tone.

What used to be framed as drug abuse was now framed as treatment. Cancer patients were speaking on camera. AIDS activists were being interviewed without being interrupted. Doctors, cautiously at first, began to say what patients had been saying for years: cannabis was helping.

And it wasn’t just AIDS and cancer anymore.

People with multiple sclerosis came forward. So did those with chronic pain and Crohn’s disease. Veterans with PTSD testified that cannabis let them sleep without pills or nightmares. Grandmothers with arthritis. Young people with epilepsy. Parents who had run out of options. Nurses who had seen it work when nothing else did.

The plant had been passed hand to hand for years. By 1995, the stories were harder to ignore. There were too many of them. Too many people helped.

The shift didn’t come all at once. But it came.

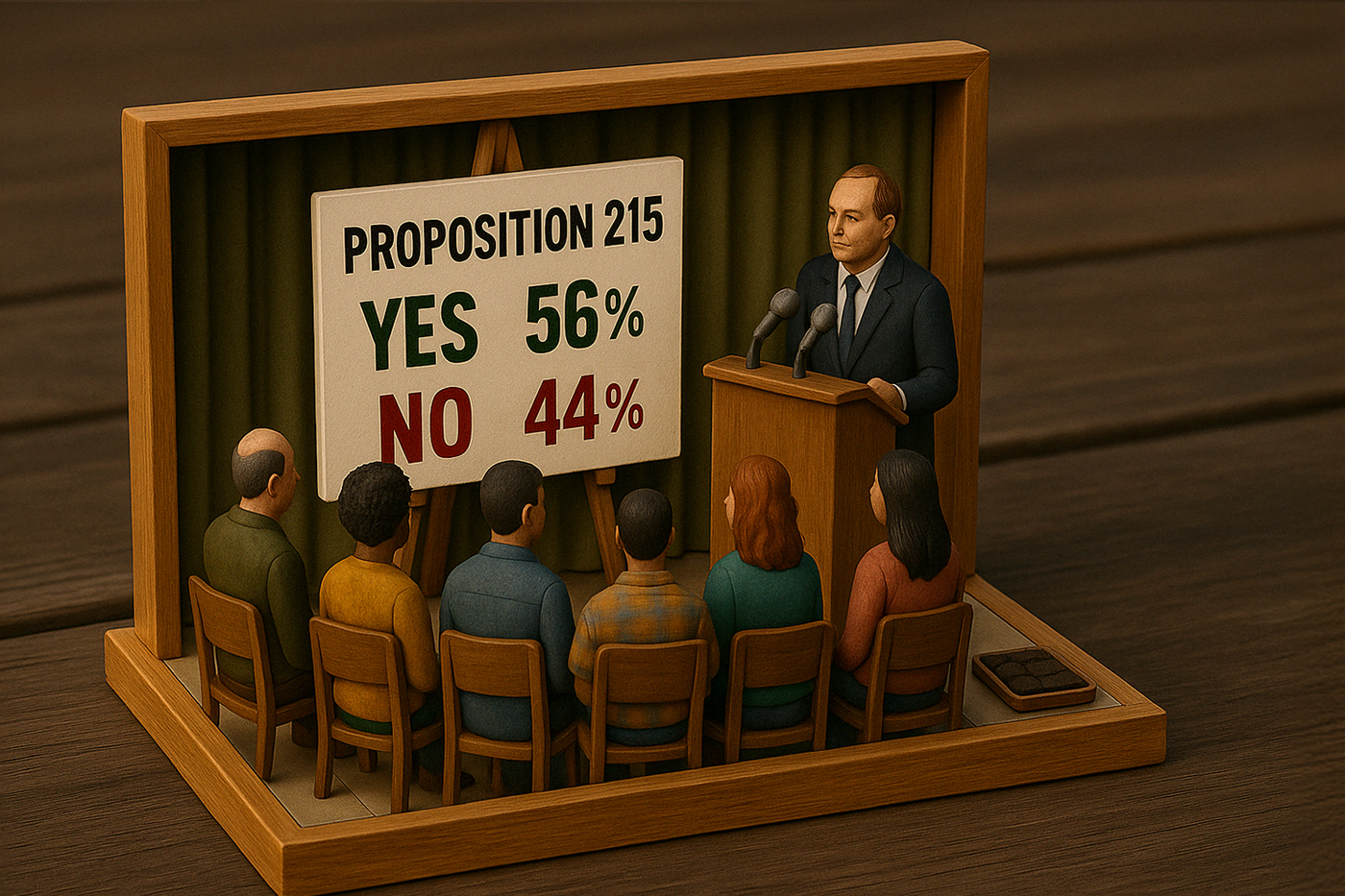

In 1996, California put Proposition 215 on the ballot. It wasn’t framed as legalization. It was framed as compassion.

The text didn’t mention stoners or dealers. It talked about patients. It used words like “relief,” “care,” and “physician recommendation.”

The measure passed. The state listened. The first of its kind in the country.

They didn’t call it weed.

They called it the Compassionate Use Act.

***

Assembly District Office, Central Valley. Spring 1996.

No windows. One printer. Two-and-a-half chairs that didn’t match the table. A polling memo lay face-up under a half-eaten bagel, and someone had scribbled “SUPPORT: 58% – strong among women over 40” in the margin.

Three men sat with their jackets off and their collars wilted. A fourth joined late and didn’t apologize.

“The church groups haven’t said a word,” said the senior staffer. “The hospice networks are sending letters. We’ve had five calls from veteran orgs this week.”

He didn’t look up from the memo. “This isn’t fringe. It’s moving.”

“Still smells like weed,” said the youngest guy, scratching the inside of his elbow. “What do we say when the sheriff’s association starts screaming?”

The senior one didn’t answer. He folded the memo in half and set it aside like it was radioactive.

“This is pressure,” said the guy with the polling numbers. “But it’s also cover.”

That got their attention.

“Everyone’s talking AIDS and cancer. People crying on KQED. We say no, and it’s heartless. We say yes, and it’s political suicide.” He pointed at the folded memo. “But we let it go to a vote, and suddenly it’s not ours anymore. It’s the people’s will.”

Silence.

The printer buzzed, then stopped.

“If we take a stance—”

“No stance,” said the senior staffer, flat. “We’re not endorsing it. We’re not condemning it. We’re respecting the process.”

The room shifted. Shoulders dropped. No one lit a cigarette, but it felt like someone should have.

“We look neutral,” said the youngest.

“No,” said the senior one. “We look humane.”

He tapped a legal pad with a capped pen. “They’ve got no name for it yet?”

“No,” said the polling guy. “Just ‘medical marijuana.’”

“Jesus,” the senior muttered. “Sounds like a narcotic and a punchline.”

He wrote something down slowly, underlining it twice: The Compassionate Use Act.

It sounded church-approved. It sounded accidental.

“If it works,” he said, “we never blocked it.”

“If it fails,” added the youngest, “we never touched it.”

Someone nodded. No vote. Just understanding.

They didn’t issue a press release. But when the calls came in, they faxed the same line:

“We support the right of patients and their doctors to explore compassionate options. We trust the voters of California to decide this matter with care.”

No names.

No quotes.

Just enough to not be remembered for the wrong thing.

When it passed, nobody made a speech. Nobody called a press conference.

The memo got filed into a drawer that never locked.

Later that week, the senior staffer circled the latest polling crosstabs with a red pen. Then he circled his own name.

Legalization wouldn’t happen overnight.

But if it did, he planned to be standing just far enough ahead of it to look brave.

***

The vote changed more than just policy.

It changed the ecosystem.

In the years that followed, cannabis clinics opened with receptionists, waiting rooms, and physician referrals. Doctors who once avoided the subject began attending conferences. Researchers applied for grants. Pharmaceutical startups formed with advisory boards and seven-figure seed rounds. Some were idealists. Some were opportunists. Most were both.

The same plant once passed in whispers was now being delivered in blister packs, formulated into tinctures, and written up in medical journals.

It didn’t happen overnight. But it happened.

Cannabis had been a symbol of rebellion. Then a tool of compassion.

Now it was becoming something else again: a product with a patient profile and a business plan.

They called it medicine.

And for the first time, the law did too.