How Cannabis Traveled from California’s Underground to the Heart of American Culture

A chronicle in 10 chapters—from borderlands and beat poets to boardrooms and billboards.

By the early 1960s, California wasn’t just a state.

It was a direction.

People moved west the way a tide pulls. Not for work. Not for land. For something softer. Something they couldn’t name but thought they’d recognize when they found it. Haight-Ashbury lit up with color and noise. Topanga Canyon filled with musicians and wanderers. Big Sur sat quiet and strange on the edge of the continent, waiting for someone to understand it.

The country was still running on rules. But here, the rules bent. The days were slower. The clothes looser. And the plant, once passed in shadows, now sat in the open. Rolled on breakfast tables. Shared at sunset. Part of the rhythm.

In the decade before, cannabis had belonged to the Beats. It had been their small rebellion—lit in cheap rooms, smoked between lines of poetry, exhaled through the cracks of a country they no longer trusted. It was how they stayed awake. How they stayed outside.

But now it had moved past rebellion. It wasn’t protest smoke anymore. It was part of something else—exploration, connection, communal experience. It was used before meditation, before songwriting, before long talks that started at midnight and ended when the sun rose.

It shared space now. With acid. With incense. With barefoot walks to nowhere. It wasn’t about escape. It was about expansion. Getting open. Getting still. Getting weird.

The joints burned slower here. Not because people were afraid—because no one was in a hurry.

California didn’t invent the movement. But it gave it room to breathe.

The music said it before the newspapers did.

By the mid-1960s, cannabis had a sound. You could hear it in Dylan’s drawl, in the sitar lines of Norwegian Wood, in the echo-laced solos of Jimi Hendrix. Songs got slower. Lyrics stretched out. Bands talked more about feeling than fact. The plant wasn’t hidden—it was in the art.

The Beatles talked about smoking with Dylan. The Rolling Stones got arrested with it in the room. Hendrix didn’t hide it. Neither did Janis Joplin, Jerry Garcia, or anyone paying attention.

Cannabis was passed backstage and burned on blankets at concerts. It didn’t belong to any one kind of person anymore. It belonged to whoever wanted to listen a little longer. Whoever wanted the night to last.

Rolling Stone wrote about the music, but also about the smoke that came with it. Not scandal. Culture. Stories about artists. About scenes. About the way the plant moved through it all like a second melody.

The plant had been a secret, a companion, a symbol. Now it was a language. A way to say I’m not part of that, without needing a speech.

It wasn’t protest anymore. And it wasn’t hiding. It was part of the show.

They came west to look inward.

By the late 1960s, the movement had spread beyond cities and sound. It reached into hills, cliffs, and dry stretches of land where people went to shed things. Belief systems. Family names. The idea of America. They came by car and by thumb. Some carried journals, others guitars. A few brought nothing at all.

Places like the Esalen Institute in Big Sur gave them something that felt like meaning. The campus sat on the edge of the world, carved into cliffs where the mountains met the Pacific without apology. The air smelled like eucalyptus, sea salt, and wood smoke. There were rope swings and open windows, notebooks left under trees, bodies soaking in hot springs that steamed above the surf.

Founded by Michael Murphy and Dick Price, Esalen blended Western psychology and Eastern philosophy. Fritz Perls walked the grounds in bare feet, teaching Gestalt therapy in real time, pulling emotion from silence. Aldous Huxley gave lectures on human potential. Joan Halifax guided people through death meditations in the fog.

They offered encounter groups, yoga, bodywork, cold plunges, LSD trials, and long days of not saying anything. You could scream. You could cry. You could sit in a room and let the stillness do the work.

Cannabis was part of the practice. Not central, but present. Rolled before breathwork. Shared on the rocks after sunrise yoga. Smoked between sessions led by therapists with no shoes. It wasn’t offered, and it wasn’t forbidden. It was just there—a tool, not a thrill.

Sometimes it helped people cry. Sometimes it helped them sit still. Sometimes it helped them leave their name behind and not pick it back up.

The plant moved differently here. It wasn’t passed in shadows. It wasn’t used to escape. It was used to get closer. To open. To listen. It became part of a spiritual grammar, alongside incense, fasting, LSD, ocean air, and hours of silence.

Esalen wasn’t the only place. There were others—less famous, less formal. Houses in Topanga, cabins near Mount Shasta, off-grid camps outside Santa Cruz. The seekers spread out. So did the plant.

They didn’t all find what they were looking for. But they found each other. And they found cannabis, waiting quietly in the middle of it all.

***

There was a man on the deck trimming marijuana with sewing scissors. His hands moved gently. Not expertly, but with the kind of attention people once gave to rosaries or stray animals. He didn’t speak much.

Inside, someone had put on a record—maybe Leonard Cohen, maybe not. I remembered the chords but not the voice. The sun hit the floorboards in long gold stripes. Someone was laughing in the kitchen, softly, like they’d just remembered something good.

The house didn’t have clocks. It had ashtrays, teacups, a shelf of half-read books. Windows without glass. Doors that never closed. Beds that didn’t belong to anyone in particular.

Someone in the hallway was on a fast. She hadn’t eaten in three days and wouldn’t say when she planned to start again. Another girl was still coming down from a tab she’d taken the night before. The air was slow and watchful. Nobody made eye contact for too long, but when they did, it held.

A woman stood barefoot in the garden, staring at a tree. She’d been there since sunrise. When I asked what she was doing, she said she was “listening to its shadow.” I didn’t ask what that meant. We weren’t asking a lot of questions then.

There was always smoke in the house. Not thick, not deliberate. Just there. Someone had rolled a joint into the sleeve of Time magazine. Someone else had a pipe carved from deer antler. No one made a show of it. Cannabis wasn’t the focus. It was just what the day tasted like.

I don’t remember breakfast. I remembered a girl crying on the floor, her hand wrapped in gauze, her hair full of flowers. No one asked why. It wasn’t that kind of morning. Later, she danced barefoot in the hallway to no music at all. Someone handed her a peach. They both smiled.

They called it a commune, but it wasn’t. It was a place to drift. To avoid things. To stay soft by staying unmade. People spoke less as the days went on. Silence became something between us, like a fourth meal.

That winter, the rains came and the canyon slid. The road cracked and half of it went with it. That spring, someone left and never came back. I forget his name. I remembered he smoked in the shower and sang songs with no words.

Everyone said they were free.

I remembered that I wasn’t so sure.

***

The signal couldn’t stay local.

By 1969, the culture that started in living rooms and backroads had moved into headlines, airwaves, and living color. CBS ran segments on communes. NBC interviewed barefoot teenagers. TIME ran a cover story on “The Hippies.” The words were cautious. The images weren’t.

Cannabis didn’t lead the story. But it was in the frame. In the background of interviews. In the air behind every song. It wasn’t named, but it was seen. Smoke drifting through festival footage. Musicians grinning. Teenagers cross-legged with red eyes and slow smiles.

And then came Woodstock.

Four hundred thousand people in a field in upstate New York. No police lines. No riots. Just music, rain, mud, and smoke moving like weather through the crowd.

And the music mattered. It wasn’t packaged. It wasn’t polished. It wasn’t brought to life by labels or broadcast deals. It was brought by the artists themselves—Hendrix, Joplin, Crosby, Santana, The Who—who arrived without handlers or sponsorships and played like the world was listening. The sets were raw and electric. Some were messy. Some were perfect. But all of them were real. No one performed like they were selling something. They performed like they believed it.

It was filmed. It was edited. It was broadcast. Not all of it—but enough. Enough for people in Ohio and Kansas and Indiana to watch it on television and ask themselves what they were really seeing.

This wasn’t the chaos they’d been warned about. This was peace. This was joy. This was harmony—disheveled, loud, stoned, but unmistakably human. No violence. No panic. Just half a million people getting high and getting along.

They didn’t all approve. But they watched. And that changed things.

The plant had been framed as danger. Now it was framed by music and sky. It wasn’t just counterculture anymore. It was culture.

What had once been hidden was now broadcast. And the country couldn’t unsee it.

***

I spent most of that Saturday behind the scaffolding. The stage crew had carved out a space with milk crates and splintered plywood, just wide enough to lie down in if you kept your knees up. Someone had taped a sign to the side that said NO DOGS / NO BABIES / NO BAD VIBES. It had already peeled off by noon.

The air smelled like wet canvas and sweet smoke. Not thick—just always there. I didn’t see anyone roll a joint that day, but I saw dozens being passed, like notes in a classroom, like something you didn’t have to explain anymore.

Somewhere, Santana was playing. I could hear the congas from behind the amps. It sounded good. Not transcendent. Not divine. Just good—tight, focused, like they’d done this before. I remember thinking it was the most professional thing I’d seen in days.

A girl nearby was braiding flowers into someone’s hair. The boy—maybe eighteen—was shirtless and shivering and looked like he hadn’t slept. He wasn’t smiling. The girl didn’t stop to ask. She just kept weaving the stems through his curls like it was the only thing that mattered.

Someone else said they’d seen Joplin crying backstage. Someone else said they’d seen God. Both things felt equally plausible.

People kept arriving. On foot, on shoulders, in twos and threes. No one was running. They just drifted in, like fog or memory.

Later, I watched a group of strangers build a small fire out of wet wood and trash paper. They took turns holding it with their bodies, shielding it from the wind like it was sacred. When it finally caught, they all clapped—not loud, just happy. Someone passed around slices of bread. Someone else sang a verse of The Weight. Everyone knew the words, but no one sang too loud. It was enough just to be part of the sound.

The ground was soft. The sky didn’t know what it wanted. A girl next to me asked if I thought the government was watching. She didn’t wait for an answer.

They called it a turning point. A signal. Proof of something good. Maybe it was. But it also felt like the edge of something—like a place you could only visit once.

I didn’t stay long after that.

I remembered the sound of the drums more than the songs. I remembered the smoke, how it hung in the air like a decision that hadn’t been made yet.

***

The party didn’t end all at once. But the sky changed.

Four months after Woodstock, they tried again. A free concert. California this time. Altamont.

The music showed up. So did the people. So did the Hell’s Angels, holding beer and pool cues, hired for security. During the Rolling Stones’ set, a man pulled a gun. The Angels pulled knives. Meredith Hunter died feet from the stage. The cameras caught it. So did the country.

The media replayed the chaos. "Rock's Darkest Day," they called it.

Then came the reminders.

The Manson murders had happened just before Woodstock. At first, they were a shock, but distant. Now, the trials began. Charles Manson's face was everywhere. The press dissected the cult, the killings, the eerie messages left behind. "Helter Skelter," scrawled in blood.

The narrative shifted.

What had looked like freedom now looked like chaos. The music was still playing, but the story had changed. Long hair meant risk. Bare feet meant danger. The same cameras that had shown smoke and song now showed blood and noise.

Cannabis hadn’t caused it. But it was close enough to blame. It showed up in headlines. In police reports. In testimony. The plant that had meant connection now meant collapse.

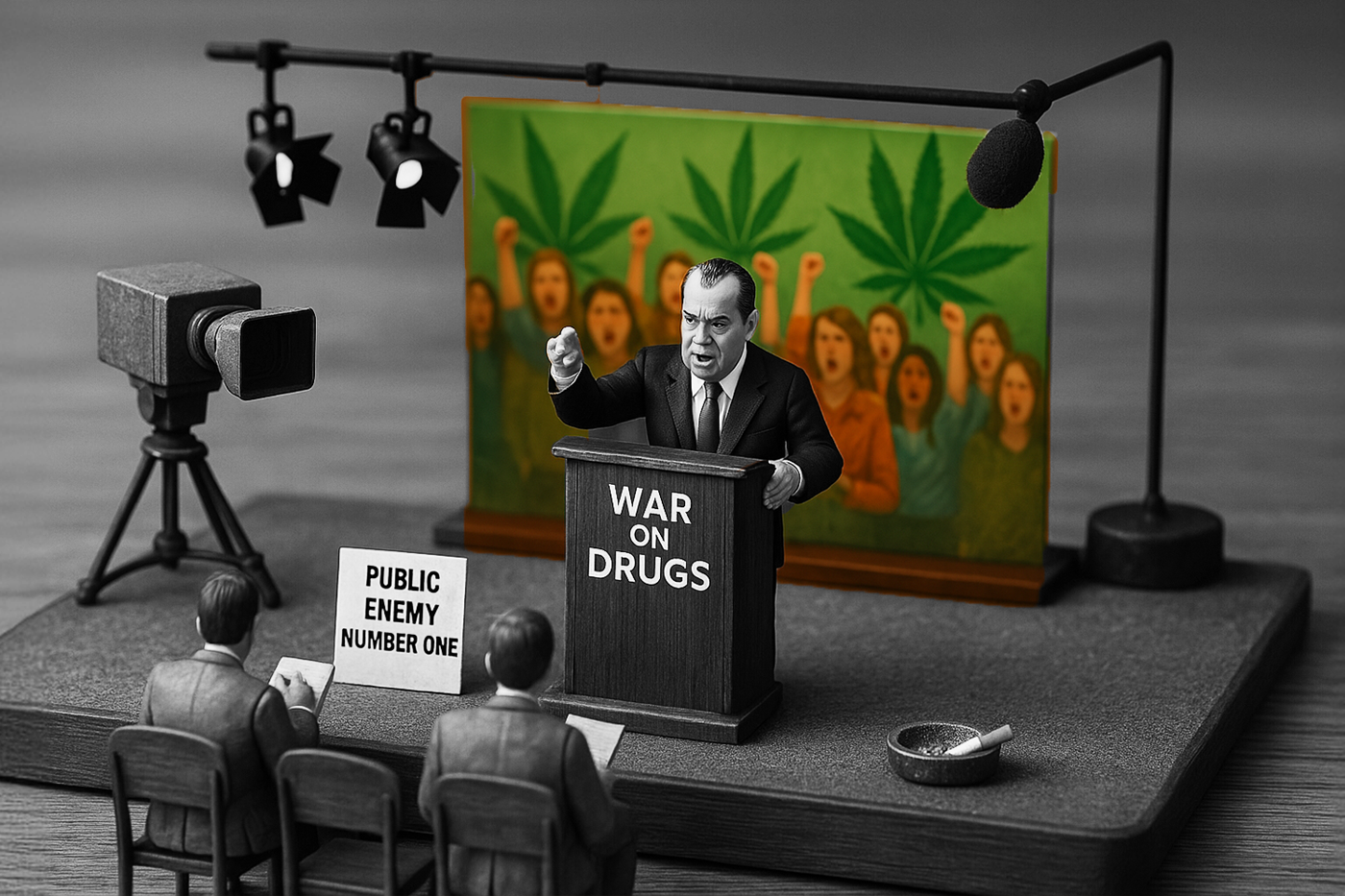

The backlash came fast. Raids. Arrests. Laws with names. The smoke was still there. But the country had turned. The dream was over. And the plant was guilty by association.

The world didn’t end. But the party was over.