How Cannabis Traveled from California’s Underground to the Heart of American Culture

A chronicle in 10 chapters—from borderlands and beat poets to boardrooms and billboards.

The smoke hadn’t vanished, but the mood had changed.

Woodstock had been joy. Then came Altamont. Then came the trial. What the cameras once called peace, they now called madness.

In Washington, they watched. The music had gotten too loud. The crowds too big. They didn’t know what to call it, but they didn’t like what it looked like.

The war was still on. The bodies still came home. In another time, they came home to parades. Now they came home to silence. To protests. To younger brothers who didn’t want to hear it. The uniforms made people uncomfortable.

And the news showed kids in fields, passing joints, walking barefoot through the country like they owned none of it and all of it at once.

They didn’t need to understand it. They needed to stop it.

The paperwork was already there. Harry Anslinger had written it decades earlier—files, reports, policy briefs, language that turned a plant into a threat. It had been about taxes then. Now it was about fear.

Cannabis was everywhere. Not the loudest thing. Not the most dangerous. But always in the picture. They circled it with red pen. They found the laws still on the books.

***

The room was kept deliberately cold. They said it helped with concentration.

The carpet was thin. The walls were paneled in something that looked like wood but wasn’t. There was a coffee service no one touched. The cups were mismatched and the sugar had caked into a brick. A single yellow legal pad sat unused at the far end of the table.

J. Edgar Hoover sat at the head, framed by the fluorescent hum and the kind of silence that meant everything was being measured. He wore a pinstriped suit that hadn’t creased and a pair of gold-rimmed glasses that hadn’t moved in twenty minutes. Two aides flanked him, identical pens, no expressions.

A man from Domestic Intelligence—Agent Merrill, Midwestern vowels, pale knuckles—cleared his throat and began to read.

“We’ve identified a cross-demographic uptick in cannabis consumption among nonconforming youth clusters,” he said. “Primarily in urban universities and municipal perimeter zones. Secondary spillover into service industries and non-vetted transportation hubs.”

He didn’t look up. The phrasing had been vetted three times before it made it to paper.

“Usage correlates with increases in loitering, curfew violations, low-grade vandalism, and tactical noncompliance. Behavioral groupings are categorized as unruly, unscheduled, and ideologically resistant.”

A pause. The sound of a pen scratching.

A man from Treasury—older, deliberate—circled something in his notes and said, “Is there a map?”

“There will be,” Merrill replied. “We’ve asked the regional offices to submit trend overlays before quarter close. Right now we’re treating it as behavioral leakage—non-directed, non-cellular.”

A chuckle—barely. “You’re saying they’re not organized, they’re just contagious.”

Merrill gave a small nod. “That’s our position, yes.”

A second man—leather attaché, likely Counterintelligence—leaned in. “Is this linked to any known groups? SDS? Panthers? Do we have crossover?”

“No formal linkages yet,” Merrill said. “Though the rhetoric overlaps. There’s evidence of symbolic borrowing. Protest theater. Anti-institutional signage. We’re reviewing chant convergence.”

Someone at the end of the table muttered, “God help us.”

Another voice—calm, legal, likely Justice Department—cut in: “And the foundation? We still have statutory teeth?”

“Yes, sir. The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 is still fully enforceable under Title 26. Further alignment with Schedule I is pending, but we’ve confirmed administrative latitude under current federal scope.”

“What about optics?” someone else asked. “We push this too fast, it becomes a speech, not a sweep.”

Hoover raised one hand—not a command, more of a punctuation.

“Use the language we already own,” he said. “Don’t change the script. Change the volume.”

There was a silence. No dissent. Just quiet agreement.

The agents exchanged folders. Merrill passed a sheet across the table. A copy of an internal memo from the Los Angeles field office: youth arrests, by district, tagged with a red stamp that read FLAGGED FOR PATTERN REVIEW.

Hoover tapped the arm of his chair.

“Do we have field discretion on language?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good,” he said. “Disruption by way of enforcement. Keep it off the front page. Make it boring.”

Someone smirked. Another wrote something they would later burn.

There was no vote. There didn’t need to be. No one requested minutes. The memo was returned to its folder. The folder was returned to a locked briefcase.

They weren’t there to escalate. They were there to standardize.

The lights buzzed overhead. The coffee went cold. No one noticed.

And by the time the room emptied, the message had taken shape:

You can’t arrest a philosophy.

But you can arrest everyone who carries it in their pocket.

***

Nixon came into office talking about law and order.

Not because he believed the country had lost its mind—but because he believed it had lost control.

By 1968, the country was in pieces. Protests on campuses. Riots in cities. Bodies in jungles. He didn’t need to fix it. He just needed to make people feel like someone was in charge again.

That was the pitch: The Silent Majority versus the noise.

Inside the West Wing, the threat wasn’t framed as ideology. It was framed as momentum. A generation moving away from obedience, away from deference, away from institutions. The words were youth culture, civil disobedience, moral decline. But the strategy was simpler.

H. R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, John Mitchell—they weren’t confused. They understood it wasn’t the music or the protests or the language that scared suburban America. It was the loss of control. It was the image of a society that no longer listened.

The ideology couldn’t be outlawed. But the behavior could.

As one aide said later: “We don’t need to beat the ideology. We just need to beat the behavior.”

Cannabis became the hook. It was visible. Familiar. It crossed class lines. It showed up in every photograph, every arrest report, every dorm room raid.

By making it the focal point, they could make the movement criminal without ever saying what they were really fighting.

They started with press briefings. Stats about drug use. Graphs that made it look like an epidemic. Language that blurred the line between users and criminals, between behavior and threat. The messaging wasn’t scientific. It was tactical.

The laws were already on the books. The public was already uneasy. The story only had to be told the right way.

And once it was, the crackdowns began.

***

They met in an office that wasn’t marked as such. A service room with the curtains drawn, west-facing, second floor. The overhead fixture buzzed faintly and gave the walls a jaundiced tint. There was a single framed photograph of the Capitol, off-center. The carpet was clean but worn flat under the chairs.

Ehrlichman arrived first, carrying a stack of folders under one arm and a rolled newspaper under the other. He removed his glasses before he sat, polished them without looking, and folded his coat neatly over the back of the chair. Haldeman came in five minutes later, said nothing, and set his briefcase down without unfastening it.

There was coffee, but it had cooled. One of the aides tried to offer sugar and was ignored.

The other men filed in quietly—Legal, Legislative, possibly Domestic Policy. No nameplates, no tape recorder, no agenda printed. Just yellow pads, pilot pens, and a pad of embossed stationery from the Eisenhower Executive Office Building.

They didn’t talk at first. They read. Ehrlichman flipped through polling data while Haldeman opened a folder marked in green: Youth Cultural Sentiment / Action Memo Draft 2B. It smelled faintly of cigarette smoke and thermographic ink.

“I’m less concerned about the substances,” Haldeman said eventually, not looking up. “More about the patterns.”

The others nodded, or blinked. It wasn’t agreement. It was rhythm.

“The issue isn’t the drug,” Ehrlichman added. “The issue is control. The issue is optics.”

They passed around sheets—Gallup data, police union notes, one page torn from a PTA newsletter in Indiana. Key words circled in pencil: disrespect, noise, loss of values.

“Youth vote’s up,” someone said. “Campus turnout. Third parties. Even the Times is softening.”

A legal aide slid a memo across the table. It was half redacted, marked INTERNAL EYES ONLY. It mentioned rising cannabis use, but not in health terms—in behavioral ones: lateness, non-participation, loss of structure.

“That’s the frame,” Haldeman said. “Not damage—drift.”

And then Ehrlichman said it, lightly, as though repeating a line from a speech not yet given:

“Look—we knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be against the war, or Black. But by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and the Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.”

No one was shocked. No one wrote it down.

He turned the phrase over in his mouth one more time, almost fondly.

“Once you have the association,” he added, “you don’t need the justification.”

They all understood. The question wasn’t whether it would work. The question was how cleanly it could be sold.

The talk shifted.

They discussed field implementation—task forces, pilot cities, sentencing language. Someone mentioned starting in Baltimore or St. Louis. “Somewhere manageable,” they said. “Somewhere photogenic, but disposable.”

One man referenced a camera angle used during the Watts coverage. Another mentioned a local sheriff who “understood the value of posture.”

They didn’t say arrests. They said contact events.

They didn’t say suppression. They said community stabilization.

There was no shouting. No urgency. Just careful pacing—like men designing a cul-de-sac or a reservoir. Something poured in slowly and meant to last.

The air smelled like old furniture and steel staples. One aide cracked his knuckle, then immediately looked sorry.

They wrapped just after the hour. No handshakes. No summary. Just the familiar soft click of folders closing.

It wasn’t justice they were after.

It was control.

***

The First Shots Fired

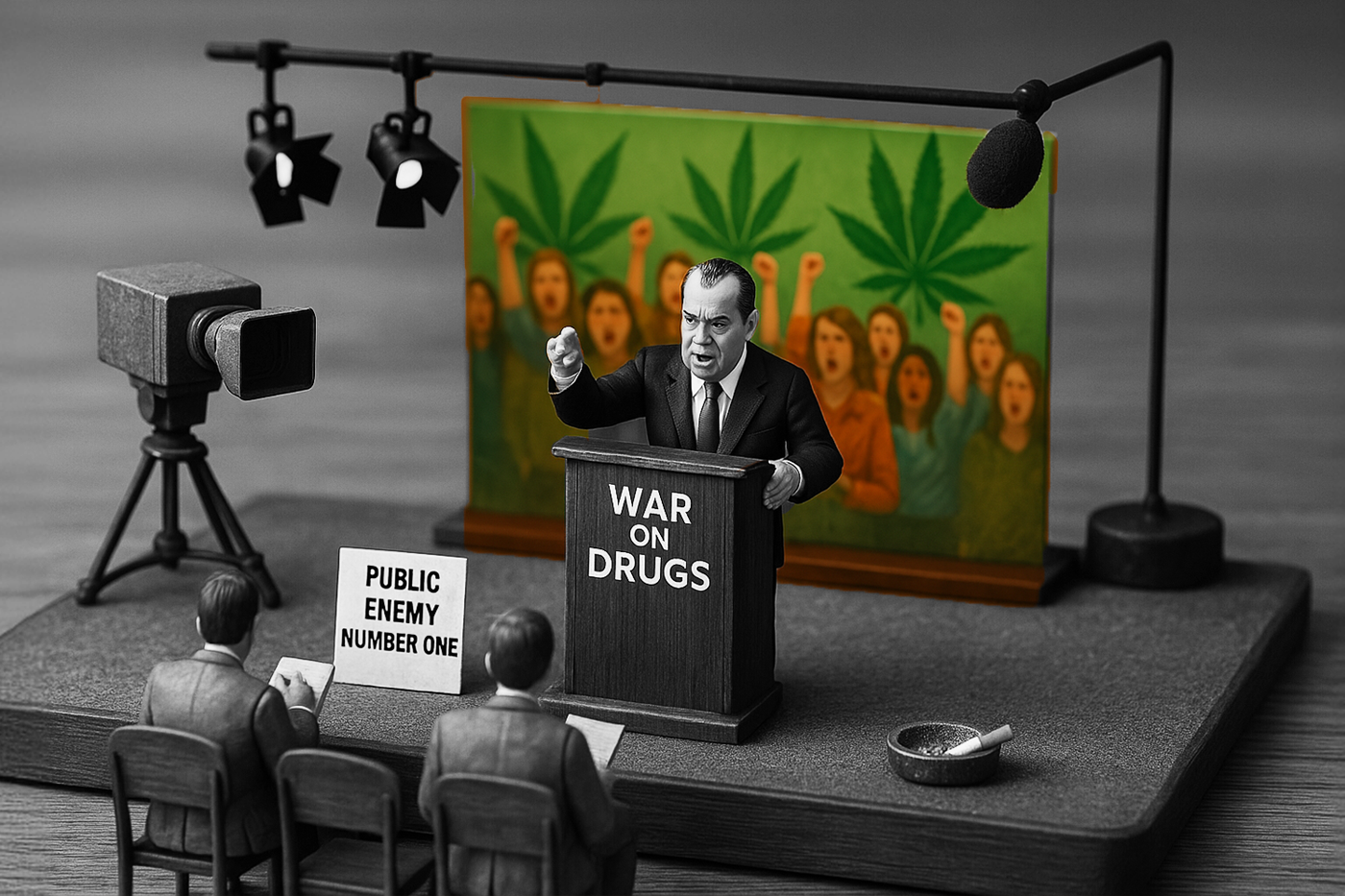

On June 17, 1971, Nixon went on camera and gave the war a name.

“America’s public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse.” That was the line. Short. Sharp. It didn’t need context. It needed headlines.

Behind the scenes, the strategy was already in motion. The year before, Congress had passed the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. Cannabis was placed in Schedule I—the highest category. High potential for abuse. No accepted medical use. The same list as heroin.

There wasn’t much debate. There wasn’t much science either. The recommendation from Nixon’s own commission—the Shafer Report—hadn’t even been released yet. When it finally came, it would argue for decriminalization. Nixon ignored it.

Cannabis had no lobby. No major institution to defend it. No corporation to protect its name. No one in the room spoke for the plant.

But the press did their job. The photos matched the message: long hair, smoke, arrest.

The public followed. Parents. Principals. Police chiefs. The story made sense to them. It sounded like order.

And then the war became real.

Police departments across the country created new task forces. The funding came quickly. There were new radios, new vans, new language—drug sweep, zero tolerance, domestic threat. The targets weren’t hard to find.

College campuses. Public parks. Apartment buildings with posters in the window and record players behind the door. Most of the arrests were for possession. That was the point.

By 1972, there were over 400,000 marijuana arrests—almost all small, almost all public, almost all visible.

It didn’t matter that the threat wasn’t real.

The laws had been passed. The narrative had been set. The raids had begun.

The laws locked into place. Quietly. Permanently.

The war had begun. Most people didn’t even realize what had been declared.

The raids would continue. The numbers would grow. New budgets. New language. New enemies. Most of them young. Most of them unarmed. Most of them high.

This wasn’t a war fought on battlefields. It was fought in neighborhoods. In classrooms. In voting booths. It didn’t need uniforms. It didn’t need truth.

It only needed permission.

The war didn’t start with a gun. It started with a press conference.